Beginnings

From Katanning Regional Business Association

The beginning of European Settlement

In the half century following its foundation in 1829, the government of the Swan River Colony could not convince the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company [2] (P&O) that Fremantle was a more viable port than Albany in the south. Though C. Y. O’Connor was to prove them wrong less than 10-years later, the experts of the time said that a suitable harbour in Fremantle, if constructed, would need constant dredging and was thus impractical to build. They suggested a better use of the governments meagre funds would be a railway that connected Perth to Albany.

A New South Welshman, Sir Anthony Hordern, applied for, and obtained, the contract to build the railway on a land grant system after he created the Western Australian Land Company in London specifically for the purpose.

On October 20th, 1886, Sir Frederick Broome turned the first sod on the construction of the Great Southern Railway in Albany, while his wife, Lady Broome, did the same thing nearly 400 kilometres away in the town of Beverley. This set-to-work two construction crews and their travelling villages that would converge, two years and four months later, at a spot four kilometres north of what is now the town of Katanning.

Two brothers, Frederick and Charles Piesse, had been following the construction of the northern half of the line, carting and erecting their portable store, trading under canvas as they went. The final resting place for this store was where the Royal Exchange Hotel now stands in Austral Terrace opposite the central station of the line and the town that was to mushroom around the shunting yards there.

It seems that even before this time, Katanning had been a natural meeting place. The biogeographical region covering most of the South-West of WA converges in the Katanning district, from the Jarrah Forests [2]to the very southern tip of the vast wheatbelt. Travel a little further inland and you cross into the Mallee. Looking east from the town centre, up Clive Street, on the horizon you can see one of the last stands of South-West jarrah before the plains begin.

Beginnings

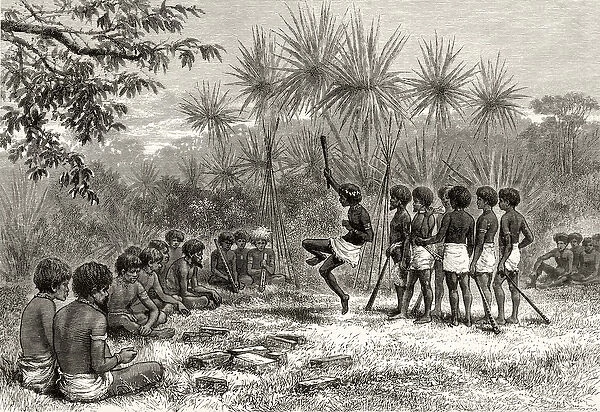

The area is also where three tribal grounds of the Noongar nation converge: Wilman, Goreng and Kaneang. These groups would meet to settle disputes, trade, and in times of plenty, share the bounty of a good season. This area is also on the broad line that divides language groups using the suffix ‘up’ (like Kojonup and Tambellup) in place names, and the groups that use ‘ing’ or ‘in’ for the same purpose (e.g. Pingaring, Jilakin, Kukerin and Nyabing)

At the time the railway was completed, little wheat was grown in the colony. Flour could be purchased at a much lower price from South Australia. A leading agriculturalist at the time, W.T. Loton, insisted that Western Australia could have a wheat industry if high quality flour mills were constructed. This view was shared by many, including Sir John Forrest, who was to become the state’s first premier.

By 1890, the Byfield family had constructed a mill in the Piesse’s original hometown of Northam. After visiting Northam, and seeing the modern roller mill in action, Charles convinced Frederick to build a similar one in Katanning.

The Piesse brothers, to use modern parlance, did not muck about. Within nine months of conceiving the project and barely 15 weeks of construction, the Premier Roller Flour Mill, started with a noise that ‘was nothing more than the humming of a well-spun top’ (as was reported on the day) in April 1891.

Beginnings

The electricity used in its operation was also supplied to homes and businesses up until 1964. As Katanning grew industries that, for their day, were world-leading relied on the power source.

The mill was adapted and upgraded several times in its lifetime as competition from other milling companies increased. It shut down for a time in the 1920’s but was then purchased and re-started by a group of townspeople. It struck trouble again in the 1970’s, before being sold to the Swan Oat Milling company; and was then closed for good in 1977.

Not for the first time, the threat of demolition loomed. However, through the efforts of the Katanning Historical Society, the building was spared. After being purchased by the Katanning Shire, the mill continued to serve as a museum, housed an arts and crafts centre, and local tourist bureau before being vacated due to safety concerns in 2008.

It was to take another inspired effort of entrepreneurial daring and vision to save the mill and extend its life into a third act. The Shire offered the building for sale for one dollar. This sale was on the condition that the buyer would develop the property in a way that would inject life into the town while preserving its heritage listing.

Today, the Premier Mill Hotel provides world class accommodation and dining for travellers who come to Katanning for business or to base in the town while exploring the region. The unique refurbishment, that includes a café and wine bar, preserves many of the details of the working mill. It won the Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage in the 2019 National Architecture Awards. The Premier Mill makes a logical first stop for anyone exploring Katanning.

It is hard to imagine, if you walk east up Clive Street past the hospital, that the whole area was once 180 acres of orchard and vineyard. Although he did not set out to be a winemaker, Frederick Piesse got wind of a government plan to contribute to the construction of a centralised winery for any district cultivating more than 60 acres of wine grapes. When the rumoured government assistance failed to materialise, Piesse pressed forward with making wine anyway. A South Australian winemaker, Carl Bungert, was hired by the Piesse brothers. The Great Southern Winery was constructed in 1902 using bricks from the Piesse’s own brickworks.

Frederick Piesse’s Great Southern Winery c1905

Wine maker Carl Bungert standing on cart.

Wine from Katanning won the C. W. Ferguson Challenge Cup for the ‘highest points in wines made from grapes grown in Western Australia’ at the Perth Royal Show in 1904. In 1908 the winery received a gold medal at the Franco-British Exhibition in London. However, after the death of Frederick Piesse in 1912 and the challenges to the business that followed, interest in making wine faded. It is also believed that the vines contracted a disease that destroyed their productivity.

After several fires, the only remaining structure is the brick distillery, with its distinctive castellated parapets giving it the appearance of a castle’s battlement tower.

Beginnings. Beginnings. Beginnings. Beginnings.